England 1586: Alyce Bradley has few choices when her father decides it is time she marry as many refuse to see her as other than the girl she once was—unruly, outspoken and close to her grandmother, a woman suspected of witchcraft. Thomas Granville, an ambitious privateer, inspires fierce loyalty in those close to him and hatred in those he has crossed. Beyond a large dowry, he is seeking a virtuous and dutiful wife. Neither he nor Alyce expect more from marriage than

mutual courtesy and respect.

Good housewives provide ere a sickness do come: Household medicine in sixteenth-century England

Until the advent of modern medicine, most ordinary medical care took place in the home, usually administered by the women of the household. Consequently, there was an expectation that women would possess skill and knowledge in the use of herbal remedies. Their medical care extended beyond the immediate household to their tenants and labourers. Thomas Tusser recognized this in Five Hundred Pointes of Good Husbandrie (first published in 1573):

Good huswiues prouides, ere an sicknes doo come,

of sundrie good things in hir house to haue some.

Good Aqua composita, Vineger tart,

Rose water and treakle, to comfort the hart.

Cold herbes in hir garden for agues that burne,that ouer strong heat to good temper may turne.

While Endiue and Suckerie, with Spinnage ynough,

All such with good pot herbes should follow the plough.

Margaret, Lady Hoby, (1571-1633) is the author of the earliest known diary written by a woman in English. A well-connected Puritan woman, she began her diary as a religious exercise but, as time progressed, she recorded her ordinary daily activities, particularly at her manor at Hackness, Yorkshire.

Her days always began with private prayers, often followed by attending those who came to her with their injuries and ailments. She seems often to have held two clinics, one in the morning either before or after her breakfast, and one in the late afternoon. She speaks of dressing the injuries, sores and cuts of her tenants and servants. Some were serious, such as the hatchet wound on the foot of her servant, Blakethorn. Despite her deep piety, Lady Hoby also attended to injuries on Sundays.

In her diary, Lady Hoby talks of reading her herbal some evenings or having it read to her by one of her women. She also made up medicines and salves as well as distilling oils and aqua vitae. Unfortunately, she never provides detail of the medicines she made or their ingredients. And although she talks often of being busy in her garden, and in one case of giving herbs to a woman from Everley to plant in her own, she does not mention what her herbs were.

Lady Hoby visited the sick at home and mentions reading to a sick maid in her house and sitting with her husband whenever he was ill. She also records attending births, both for family members and tenants.

That Lady Hoby was given respect for her skills is obvious as in August 1601 a child, presumably a newborn infant, was brought to her. The child had been born with ‘no fundiment’. Lady Hoby was asked to cut the child to see if a rectal passage could be found which she did to no avail. She mentions no more of the incident but one would assume the child died.

We can gain some idea of the range of medicines and remedies that could be made at home from the papers of

Grace, Lady Mildmay (c.1552–1620). She is noted as having written the earliest known autobiography of an English woman. She bequeathed to her daughter over 2,000 medical papers and several books, as well as devotional meditations. The inventory of her stillroom is almost industrial in its extent and organization. Her extensive collection of ingredients included herbs, seeds, spices, gums and flowers as well as metals and minerals. She made juleps, syrups, cordials, oils and tinctures and also prescribed purges, ointments, plasters and bloodletting.

Lady Mildmay’s understanding of illness was based on the theory of humours and her treatments aimed to restore the body’s humours to balance. She did not perform surgery of any sort nor does she mention attending childbirths, visiting the poor or physically nursing the sick. She did practice her medicine daily, possibly having patients come to her at her residence the way Lady Hoby did.

Like most women, her education in household medicine had taken place at home. She was taught by a Mrs Hamblyn, her father’s niece. As well as direct instruction, Mrs Hamblyn encouraged Grace to read books like A Neww Herball by William Turner (1551) which could be used to identify herbs and their properties and uses.

Stillrooms, where many of these medications were made, were common in manor houses. When

Sabine Johnson (c1521-1597?), the wife of John Johnson, a draper and wool stapler, moved to the Old Manor House at Glapthorn, Northamptonshire she requested that her brother-in law Otwell Johnson obtain articles for use in the stillroom: a still, a mortar and pestle, and a chafing bottle. Sabine also ordered seeds and herbs for her gardens. While there is little detail of her medical care of the family, the health of the household was mentioned in almost every letter she wrote.

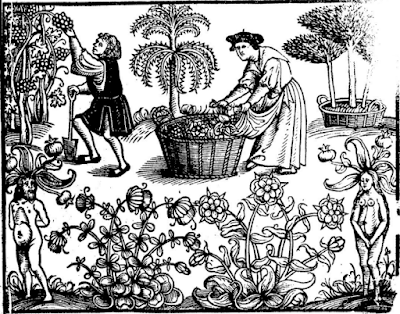

Frontispiece of the The grete herball (1526), popular throughout the sixteenth century

Herbals published in the sixteenth century described a range of herbs and their uses including information on the qualities of the herbs and when best to harvest them according to their nature and the alignment of the stars. As the century progressed, books intended for the general public simply listed medical conditions and methods of dealing with them.

The Widowes Treasure (1595), contains a wonderful collection of handy hints as well as medical advice and recipes from confectionary, scented oils, dyes, syrups and cakes to a range of medicinal recipes much like the many personal recipe or ‘receipt books’ kept by women that remain from the seventeenth century.

Women like Margaret Hoby, Grace Mildmay and Sabine Johnson offered medicines and treatments as part of their care for those within their households and on their estates, no money changed hands. Their services, particularly in rural areas where there were few if any doctors, filled a need and were not seen as being in competition with the professional medical men.

Most housewives at all levels of society would have had their own favoured remedies. Many, particularly those at the lower levels of society, also had their aliments treated by local herb wives or cunning men and women. In fiction, on occasions, women’s herbal and medical knowledge and skills is enough to make them targets of those intent on sniffing out witchcraft in their communities.

This makes for a compelling story but is not a reflection of reality. It was rare even for cunning folk to be accused and tried of crimes involving witchcraft. As modern scholarship has shown, accusations of witchcraft arose for myriad interrelated reasons.

Skill with herbs and healing was an expected part of a woman’s domain, a legitimate and essential element of a good housewife’s skills, and fitted well within nurturing role expected of women.

Catherine Meyrick

Select Bibliography

Davies, Owen Cunning-Folk: Popular Magic in English History. New York : Hambledon and London, 2003.

Moody, Joanna The Private Life of an Elizabethan Lady: The Diary of Lady Margaret Hoby, 1599-1605. Stroud: Sutton, 1998

Pollock, Linda With Faith and Physic: The Life of a Tudor Gentlewoman, Lady Grace Mildmay, 1552-1620. London: Collins & Brown, 1993.

Sharpe, J. A. Instruments of Darkness : Witchcraft in Early Modern England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996.

Winchester, Barbara Tudor Family Portrait. London: Johnathan Cape, 1955.

# # #

About the Author

Catherine Meyrick lives in Melbourne, Australia but grew up in Ballarat, a large regional city steeped in history. A former customer service librarian at her local library, she has a Master of Arts in history and is also an obsessive genealogist. The lives of Margaret Hoby and Sabine Saunders provided inspiration for some of the elements in Catherine’s novel, The Bridled Tongue, which also follows a witchcraft trial from suspicion and accusation to trial and beyond. Catherine has written two other novels.

Forsaking All Other is set, like

The Bridled Tongue, in England in the 1580s. Her latest novel

Cold Blows the Wind is set in Hobart Town, Tasmania in the years around 1880 and is based on fact. Find out more at Catherine’s website

https://catherinemeyrick.com/ and follow her on

Facebook and Twitter

@cameyrick1