In an underground labyrinth a lost soul wanders, waiting for revenge, waiting for love…

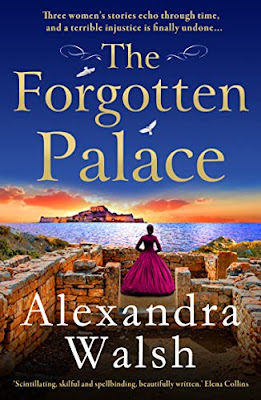

The Lost Goddesses of Ancient Crete by Alexandra Walsh

Both women find themselves drawn to the island of Crete, origin of the legend of the fearsome Minotaur. As Eloise learns about the story from her late father-in-law’s notebooks and journals, Alice has a more first-hand experience, taking part in the archaeological dig at Knossos, the palace believed to have housed the labyrinth home of the Minotaur, run by Arthur Evans.

This dig was a real event, as was the person of the indominable Arthur Evans who drew the palace of King Minos and the Minotaur from the ancient earth of Crete. Until Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in November 1922, Knossos was one of the most famous archaeological digs of its time. Arthur claimed he was not in the business of proving the classical scholars, Homer and Ovid, correct, what he was looking for was an ancient form of writing which would reveal the secrets of the Mycenaean world as hieroglyphics had given insight into the antiquity of Ancient Egypt.

Evans’s desire to discover this elusive piece of the archaeological puzzle was inspired by an event that had taken place thirteen years earlier. On 14 June 1873, in Hissarlik, Turkey, a discovery was made that would cause wonder and controversy. German businessman and amateur archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann and his wife, Sophia, discovered what they believed to be Troy, the site of the legendary battle between Achilles and Hector, the home of the remarkable story of the Trojan horse, the place of Helen and Paris’s doomed love story.

Schliemann had been excavating the site since 1870 and in total uncovered nine lost cities but the day before he was due to finish his dig he discovered a trove of gold. As he and his wife pulled these glittering artefacts from the soil he believed he had discovered Priam’s Treasure. As news of this incredible discovery travelled the world Sophia Schliemann was famously photographed wearing what they believed were ‘Helen’s jewels’.

When Schliemann went on to dig in Mycenae in 1876 and discover what he believed was the Golden Death Mask of Agamemnon, Evans watched the case with interest. However, in his scholarly and detailed mind, while Schliemann had uncovered great treasures of huge interest, Evans believed there was a vital component of the past missing from his discoveries. Where was the writing?

If these cities were indeed the remains of the great civilisations of ancient Greece, the backbone of the tales of Homer and Ovid, then they would have been huge administrative hubs full of thriving businesses with a culture all of their own. If this was the case, there had to be some form of writing. As yet, there were no clues but Evans felt sure some form of language must have been recorded somewhere and it was a matter of finding it.

This led Evans to evaluate all he had discovered throughout his many years of travelling and excavating. Several of his own pieces had marks on them which he believed could be writing and as he investigated further each seemed to lead to Crete. The more he researched, the more convinced he became that this was where the answer lay, hidden underground, waiting to reveal its secrets.

When Evans was finally able to excavate in Crete in 1900, he began to uncover what he believed were seal stones – small tablets used by scribes which were attached to goods describing the contents of jars, parcels etc – as well as markings on walls and vessels. Evans was quick to establish there were two distinct styles of writing which were remarkably different in their composition. Evans named them Linear A and Linear B. Linear A was made up of lines, similar to Roman writing, while Linear B was made of pictorial images, similar to hieroglyphs.

By the time the dig was complete, Evans and his team had discovered over one thousand tablets, a remarkable resource which was one of the greatest finds of the Knossos excavation. However, it would take another fifty years to decipher the secrets of Linear B, something Arthur Evans would not live to witness. The main contributors to the deciphering of the hieroglyphic language were Alice Kober, Michael Ventris, John Chadwick and Emmett L Bennett. Linear A has not yet been translated and it secrets remain a tantalising mystery. However, Linear B has given scholars a wealth of day-to-day information about the lost Bronze Age civilisation of the Minoans, including details of its deities.

The Linear B tablets name many of the traditional Greek gods: Zeus, Ares, Dionysus, Apollo, Poseidon, Hera and Artemis. For some scholars the inclusion of Dionysus, god of wine, was a surprise as it had long been believed he was a later addition to the Olympic Pantheon. The biggest surprise, however, were the number of goddesses who had been worshipped and whose names have since disappeared from history.

The question is: why? One theory is that by the time the classical Greek scholars were writing, the names of these deities had already faded from the public consciousness. The Minoans or Mycenaeans, as Evans named them, lived from 3500 to 1100 BC. Homer was writing in the seventh century BC and Ovid in the eighth century AD, which is an enormous time span. There is also the possibility that with the destruction of the Minoan civilisation, the names were simply forgotten. In an attempt to give some balance back to the lost pantheon, here are more details of the missing goddesses and the women who were vital to the religion of the Minoans.

The Snake Goddess, whose figurines had been discovered at the Knossos dig in 1903 is the most famous of the lost goddesses. Within the Heraklion Museum are many examples of this famous woman. She stands in bare-breasted magnificence, with snakes winding around her arms, wearing intricately patterned skirts and, in some depictions, with a cat balanced in her head. She was thought to have been the goddess of hearth, home and the purification of water. Whoever she was, her image appears in its hundreds and perhaps one of the names of the lost goddesses should be attributed to her. Sadly, we shall never know.

Another intriguing missing goddess is Diwia, the female equivalent of Zeus, the king of the gods. Would she have been his consort or a ruler of equal status? Unfortunately, there is no more information to be found. Then there is Posidaeia the female counterpart of Poseidon. He is the god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses and features heavily in the most famous myth set of Crete, the story of the Minotaur. Is it possible his female counterpart may have played a part of the tale that has since been lost?

Other unknown goddesses include Komawenteia – translated as Long-haired Goddess, along with Pipituna and Manasa, both unknown before the translation of Linear B.

Another term that was prolific throughout the translations was Potnia which is thought to mean Mistress or Lady and was an epithet for numerous deities or important priestesses. There is an extensive list of female deities including: Potnia Hippeia – Mistress of the Horses, Potnia of Sitos – Mistress of Grain and perhaps the most interesting, Potnia of the Labyrinth.

Along with the Snake Goddess, Evans discovered a huge number of depictions of the fertility goddess, Mater Theia translated to the Mother Goddess or Mother of the Gods. This prompted Evans to try and create a sense of order within the worshiping habits of the Minoans, even before the Linear B tablets had been translated and her name was discovered.

In many ways, Evans was a brilliant man but he was also a product of his age. He was a wealthy Victorian gentleman who, perhaps, believed he knew better than anyone else. Therefore, when he hypothesised, his opinion was respected even if there was little or no evidence to corroborate his theories. His views influenced beliefs for many years and his suggestion was that at the height of its power, Knossos was ruled by a priest king and his consort a priestess queen, possibly Mater Theia.

His scant evidence in creating this theory was drawn from the frescoes he discovered. They show a variety of women in elaborate, processional robes, men dressed as princes and, of course, the famous bull dancers who appeared to leap over bulls for sport. Evans may have been correct in his hypothesis but we will never be able to prove it. Other scholars believe the high priestess was a divine solar figure, which could be influenced by Pasiphaë, the Minotaur’s mother, who in the myth, was the daughter of the sun god, Helios. The Hungarian scholar Károly Kerényi believed the most important goddess was Ariadne and she was the Mistress of the Labyrinth who was identified in the Linear B tablets.

Whatever the truth behind these intriguing missing women, the frescoes, the seal stones and the images discovered in the ruins of this once-great civilisation show a culture that worshipped women with the same reverence and fervour as men. Perhaps one day, the tantalising truths of Linear A will be revealed and the whole story of these women will be revealed.

Alexandra Walsh

# # #

About the Author

Alexandra Walsh is a bestselling author of the dual timeline women’s fiction. Her books range from the 15th and 16th centuries to the Victorian era and are inspired by the hidden voices of women that have been lost over the centuries. The Marquess House Saga offers an alternative view of the Tudor and early Stuart eras, while The Wind Chime and The Music Makers explore different aspects of Victorian society. Formerly, a journalist for over 25 years, writing for many national newspapers and magazines; Alexandra also worked in the TV and film industries as an associate producer, director, script writer and mentor for the MA Screen Writing course at the prestigious London Film School. She is a member of The Society of Authors and The Historical Writers Association. For updates and more information visit her website: www.alexandrawalsh.com or follow her on Facebook and Twitter @purplemermaid25

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting