A magnificently illustrated oversize book that uses art to illuminate the lives of medieval women, from peasants to queens

Understanding Medieval Women Through Art

The medieval period is a time that captures popular imagination. It is no surprise that the fantasy genre we are used to seeing in films and television and within books often set themselves in the Middle Ages - a time of glorious knights, beautiful damsels, and a love for stories with dragons and mythical beasts. But when we want to turn to the real history behind these settings and learn more about what medieval life was really like, we can sometimes hit a brick wall. Written sources were largely written by men and were concerned with religious and political matters, often to the exclusion of women. How, then, do we find out how a medieval woman may have spent her day?

One obvious answer can be easily overlooked: artwork. Medieval Europe was an exceedingly visual culture, with art decorating their tableware, the walls of their homes and churches, their mirrors, their furniture, their books. Art was made by anyone for everyone. One did not have to be educated or literature to pick up a paint brush or sew a cushion, and as the centuries progressed and industry flourished, there were plenty of opportunities in the world of work to choose a more creative career.

Peasant women were abundantly depicted in art when they are otherwise overlooked in many written sources. Marginalia of manuscripts very often showed scenes of domestic life, and women are found baking bread, making pasta, feeding farm animals and spinning threads. As the book trade developed in the later Middle Ages, some women who had moved to the blooming towns and cities found opportunities to work as illustrators of these manuscripts, leaving their marks on books they would never otherwise have come into contact with.

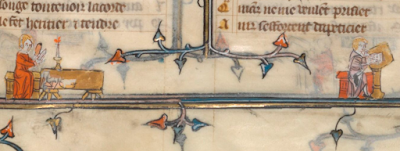

By creating such art, we are able to trace the existence of lower-class women who may otherwise have been lost to history. One well-known manuscript artist was Jeanne de Montbaston, who worked for many years as an illustrator alongside her husband Richard in Paris during the fourteenth century. The couple decorated at least 50 manuscripts that have survived today, working together and separately.

Jeanne and Richard Montbaston at work, from the Roman de la Rose

(Wikimedia Commons)

Their slightly different styles have allowed us to identify which images Jeanne was solely responsible for, and gives us a wonderful insight into her skill. One manuscript features a marvellous self-portrait of the two at work. Because Richard died before Jeanne, we know her name; in order to continue working as a single woman, she had to swear an official oath with the University of Paris. If she had predeceased her husband, we would never have known her name, but she still would have left her mark in the little figure of herself in the margins of a page.

But artists were not only from the lower classes, and one may be surprised to hear that many artists were religious women. Sequestered away in their nunneries and abbeys, religious women usually had a unique opportunity to gain a much higher education than their lay sisters. Most religious orders taught their nuns to read so that they could understand religious texts, and many consequentially learnt to write, too.

Although much of a nun’s day was expected to be devoted to prayer, idle hands were thought to encourage sin and so they needed another outlet to direct their attentions. Creating something with their own hands was seen as a healthy activity, and so nuns were told to sew altarpieces and religious garments, to copy out religious texts to fill their libraries, and decorate these books with beautiful, holy imagery.

Very many of these religious women signed their own works, and there is a plethora of self-portraits of nuns that survive from these manuscripts. Through this, we manage to have snippets of lives where records otherwise do not survive - one of the first signed self-portraits of a Western woman was created by a German nun named Guda in the 12th century.

Guda Homiliar - Univ.bib Frankfurt Barth42 f110v (detail)

(Wikimedia Commons)

Women were not only creating art, but they were expected to be influenced and shaped by it too. Noblewomen were even more surrounded by art than their lower-class counterparts, with vast castle walls to fill with tapestries and everyday items like mirror cases and storage chests carved and painted with pictures. Noblewomen had very high expectations placed upon their behaviour, and so the art that surrounded them was often meant to guide them and remind them to behave meekly and properly.

Demure women gazed down from portraits, saintly women watched over them in church stained-glass windows, and the books gifted to them depicted their own visage knelt in prayer. Noblewomen are shown as powerful, benevolent figures who guide their children and husbands with their mercy and charity.

Art held a vital important to medieval people, and so we have to consider it when trying to uncover the lives of people who lived centuries ago.

Art held a vital important to medieval people, and so we have to consider it when trying to uncover the lives of people who lived centuries ago.

Women’s voices are so often silent or silenced in the written record, and so art can tell us so much that may otherwise be lost. Through this art that they created, were depicted in, and were influenced by, we can start to unpick what life was really like for a woman in medieval Europe.

Gemma Hollman

# # #

About the Author

Gemma Hollman is a historian and author who specialises in late medieval English history. A Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, her first book 'Royal Witches' was published in 2019 and her second book 'The Queen and the Mistress' was released in November 2022. She has a particular interest in the plethora of strong, intriguing and complicated women from the medieval period, a time she had always been taught was dominated by men. Gemma also works full-time in the heritage industry whilst running her historical blog, Just History Posts, which explores all periods of history in more depth. Find out more at Gemma's website https://justhistoryposts.com/ and find her on Facebook and Twitter @GemmaHAuthor and @JustHistoryPost

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting