Available for pre-order from

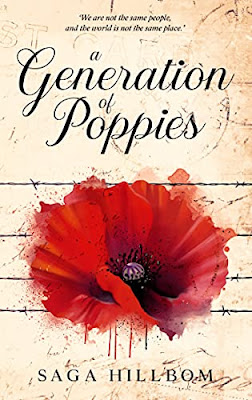

The First World War casts its shadow over seventeen-year-old Rosalie Wilkes’ idyllic life. Unwilling to sit idle, Rosalie lies about her age and signs up as a voluntary Red Cross nurse. Stationed at a hospital in Rouen, France, she has to face the consequences of modern warfare.

Researching A Generation of Poppies has been a two-step process, seeing as the book I am about to release is a second, partly rewritten and heavily revised edition. I did most of the rudimentary research four, five years ago, and have then had to come back and dig much deeper.

There is, obviously, a vast difference between researching the 15th century—which was the time period of my last novel, Princess of Thorns—and researching the First World War. To begin with, the amount of source material from the early 1900s is overwhelming compared to the number of sources concerning the last Plantagenets and early Tudors.

I found this to be both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, there were countless more perspectives and greater detail to be found; on the other hand, those perspectives and details were often tricky to pick and choose from. They also limited the narrative liberties I allowed myself to take. For example, soldiers could not arrive at a hospital with injuries from Chlorine gas when this type of gas was not introduced until the following week in the chronology.

Unfortunately, I wrote the first edition of A Generation of Poppies with a less careful approach to historical accuracy, meaning the plot often disagreed slightly with real dates and events. I had to make substantial changes to the structure of the novel in an attempt to align the story with the actual war. This was also the case regarding details of terminology and everyday life. I distinctly remember removing a certain type of lamp from several scenes as it was not yet commonly used at the time.

Another difference between researching Princess of Thorns and A Generation of Poppies is the kind of sources I used. Unlike the Wars of the Roses, World War One offers not just photographs and an abundance of artefacts but countless personal testimonies. The last veterans who served in the war have been dead for around a decade, but recorded interviews with them are easy to access.

Another difference between researching Princess of Thorns and A Generation of Poppies is the kind of sources I used. Unlike the Wars of the Roses, World War One offers not just photographs and an abundance of artefacts but countless personal testimonies. The last veterans who served in the war have been dead for around a decade, but recorded interviews with them are easy to access.

I found the archives of the Imperial War Museum and the BBC incredibly useful when trying to understand World War One from the perspectives of soldiers and civilians fighting on both sides of the conflict. The interviews I listened to were recorded in the second half of the twentieth century, when the war was naturally a fresher memory than it is today, and you can tell from the way the veterans speak. Not only did these recordings help me gain perspective for my research, but they also provided me with inspiration for added scenes and minor characters.

As for letters and photos, the National Archives as well as private individuals have been a great help. One of the pictures I spent the longest looking at was a photograph of what is with all probability the No 2 Red Cross Hospital in Rouen.

As for letters and photos, the National Archives as well as private individuals have been a great help. One of the pictures I spent the longest looking at was a photograph of what is with all probability the No 2 Red Cross Hospital in Rouen.

Eventually, I concluded that the building was indeed the hospital featured early in A Generation of Poppies, which was gratifying since I could then base my descriptions on something tangible. The most important letter I read was by the author Henry William Williamson (1895-1977). By researching Williamson’s time in the army I could establish that my secondary character Mark Crewel, who had to experience the Christmas truce of 1914, should serve in the London Rifle Brigade. Speaking of army units, converting British military terminology to French proved something of a challenge, but I was lucky to find a handy chart.

Visiting relevant historical sites has unfortunately not been an option for me due to the pandemic. Once travelling restrictions have lifted and I have the spare time, though, I look forward to taking a trip to France and Belgium to visit battlefields and memorials. While documents and old photographs can often provide more useful details for a novel, I think historical sites give you a certain feeling that is difficult to come by.

To finish off this guest post, I want to mention the amount of research that never makes it into a novel. Most authors of historical fiction—and authors in other genres—probably recognise that only a fraction of everything they learn about an era or person ends up featuring in their books.

Visiting relevant historical sites has unfortunately not been an option for me due to the pandemic. Once travelling restrictions have lifted and I have the spare time, though, I look forward to taking a trip to France and Belgium to visit battlefields and memorials. While documents and old photographs can often provide more useful details for a novel, I think historical sites give you a certain feeling that is difficult to come by.

To finish off this guest post, I want to mention the amount of research that never makes it into a novel. Most authors of historical fiction—and authors in other genres—probably recognise that only a fraction of everything they learn about an era or person ends up featuring in their books.

I myself spent months researching the aeroplanes and flying aces of World War One (Manfred von Richthofen’s autobiography and Alber Ball’s love letters were gold mines) but only wrote briefly about the topic. In my experience that is not a bad thing, though. What might at first seem like a waste of time can lead us on to new interesting discoveries, and research should never be rushed through.

See Also:

Saga Hillbom

# # #

About the Author

Saga Hillbom is the self-published author of four historical novels, including Princess of Thorns, City of Bronze City of Silver, Today Dauphine Tomorrow Nothing, and A Generation of Poppies. She is currently studying history in Lund, Sweden, where she lives with her family. When not writing or reading, Saga enjoys painting, cooking, spending time outside, and watching old movies.. To find out more, visit her website sagahillbom.blog and follow Saga on Twitter @sagahillbom02

See Also:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting