My Research: New York City’s Times Square, a Century Ago

My new novel, The Orchid Hour, takes place in 1923 in New York City. A young widow, Zia De Luca, is caught up in a secret nightclub that one can only reach through a certain florist on a cobblestone street. That little-known street runs one block in Greenwich Village.

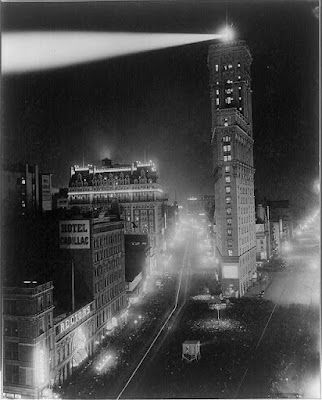

But while much of the action in my suspense novel takes place in the downtown neighborhoods of Little Italy and Greenwich Village, the story also takes Zia and other main characters to New York City’s Times Square, the area surrounding Broadway’s Theatre District.

While researching my novel, I was struck by the fact that while Broadway and Times Square were already famous throughout America—and beyond—in the 1920s, there were some key differences. It was a relatively new phenomenon. Right after the Civil War, that part of Manhattan was little but undeveloped countryside. But by 1900, the first theatres had opened.

That year, people boarded trolley cars to get to Oscar Hammerstein’s new Victoria Theatre with its 1,000 seats. A decade later, the subways were running in the city, and that opened the area to many more excited theatregoers.

At first, these large, ornate, Italian Renaissance-inspired buildings—some of which are hosting plays today—served as showcases for the latest productions from Europe. The book Greater Gotham: A History of New York said:

“Gotham was the port of entry for English comedies of manners, naughty French farces, opulent Viennese operettas, or serious dramas by Ibsen or Shaw—which, after getting their initial staging on Broadway, were then conveyed by New York producers to the nation’s theaters and concert halls, rather as New York bankers funneled European capital to the nation’s industries.”

Several forces hit Broadway in the first two decades of the twentieth century. First was the popularity of the raucous comic entertainment dubbed vaudeville, radiating out from the Palace Theatre, at 47th Street and Broadway.

Second was the arrival of Florenz Ziegfield, the impresario who took the Folies Bergère of Paris and Americanized it with the “Ziegfeld Follies,” revues featuring gorgeous showgirls and comedians like Will Rogers, W.C. Fields and Fannie Brice. The third trend was the emergence of the serious American playwright, led by Eugene O’Neill, with such early successes as The Emperor Jones and Anna Christie.

The restaurants that had catered to the Astors and the Vanderbilts, such as Delmonico’s, shut down. With no wine or liquor to be had, patrons shifted to at-home dining to secretly imbibe without fear of raids. Ziegfeld’s “Midnight Frolic,” the after-curtain-call revue on top of the New Amsterdam, complete with a glass walkway that would allow chorus girls to dance above the audience, closed in 1922. Patrons didn’t want to ogle showgirls without a glass in their hand.

This became the era of the speakeasy and the nightclub, the many illegal drinking establishments in the city. While the New York police were reluctant to spend all their time padlocking saloons—and the courts couldn’t handle the floods of arrests—a speakeasy owner took a chance opening for business.

In my novel, 'The Orchid Hour' is one of those secret nightclubs. The storyline travels to three different places that were on the fringes of Times Square in 1923, and I’ll delve into each a bit more here.

The El Fey Club

When the United States enacted Prohibition, it created a Gold Rush for not only the entrenched criminal gangs but also people who were eager to cash in on sudden opportunity. A leading example of the latter group is Larry Fay. Not a lot is known about Fay, who was the inspiration for Jimmy Cagney’s character in The Roaring Twenties.

Some say he was born in Ireland. The most famous story of his early career: Fay was driving a taxi when one night a desperate customer paid him to drive 400 miles from New York City to Montreal--and back--so the man could bring a delivery of whiskey to the city. Fay joined the action, buying a few bottles himself and re-selling in New York at a huge profit. He’d make a reported half a million dollars through bootlegging and used it to start a fleet of taxis before opening his own nightclubs.

The most well-known is The El Fey Club. After seeing a play on Broadway, people could go to the El Fay for a drink. To connoisseurs of Prohibition history, the peak location was West 47th Street, with actress Texas Guinan as the hostess. As my novel takes place a little earlier than Fay’s partnership with Texas Guinan, I set a part of a chapter in the club’s earlier location: the second floor of a nondescript building on West 46th street. Larry Fay figured out fast that he had to do more than serve alcohol. Literally hundreds of speakeasies were springing up to do that. He hired a Broadway casting director and public relations man, Nils Granlund, to make it more of a nightclub. (I was able to get my hands on Granlund’s memoir, Blondes, Brunettes, and Bullets). Patrons could drink and dance--and sing along to the 1923 sensation: “Yes, We Have No Bananas.”

Hubert’s Flea Circus

Coney Island, at the tip of Brooklyn, was at its peak during the first two decades of the 20th century. The Wonder Wheel was built in 1920. The year 1923 saw the creation of the famous boardwalk and the opening of the beaches to the public. During the summer heatwaves, pre-air conditioning, people would sleep on Coney Island’s beach.

Along with the Ferris wheels and dance halls, what drew a great many people to Coney Island were the attractions featuring the unusual, whether it was to see Dr. Couney’s incubators filled with tiny babies or the politically incorrect termed “freaks.” Among the “bearded ladies” and sword swallowers and Siamese Twins was a phenomenon known as the flea circus.

In the 1920s, “Hubert’s Museum,” drawn from Coney Island to Times Square, opened at 234 West 42nd Street, between 7th and 8th Avenues. It stayed open for decades, and its façade can be seen in the film Midnight Cowboy.

Were there actually fleas that could perform? Oh yes indeed. According to The New York Times: “There’s the triumvirate of Napoleon, Marcus and Caesar, each pulling a contemporary conveyance of war; Prince Henry, who ‘juggles’ a ball with his six legs; Rudolph, who rotates a miniature merry-go-round 300 times his weight; and Petey and Peaches, ‘dancers’ wearing ‘skirts’ (who end up looking more like hermit crabs).”

Lindy’s Delicatessen

At 1626 Broadway, at the northeast corner of 49th Street, was Lindy’s, a delicatessen that in the 1920s was the favorite dining spot for newspaper reporters and gangsters. It was opened by Leo "Lindy" Lindemann and his wife Clara in 1921. Lindy’s cheesecake, dubbed “ambrosia” by Harpo Marx, was so famous that Nathan Detroit and Sky Masterson sing about it in Guys and Dolls.

Arnold Rothstein, the gambler dubbed The Brain by his admiring rivals for his knowledge of the odds and his legendary crimes such as “fixing” the World Series, made Lindy’s his unofficial “headquarters.” He took calls and messages and held business meetings at a customary table. But he never drank alcohol, at Lindy’s or anywhere else. The man who became a millionaire during Prohibition only ordered milk.

Nancy Bilyeau

# # #

About the Author

Nancy Bilyeau is a magazine editor turned historical novelist. She followed her award-winning trilogy of historical thrillers set in Tudor England, 'The Crown,' 'The Chalice,' and 'The Tapestry,' with a book taking place in turn-of-the-century New York City, 'Dreamland.' She tapped into her French Huguenot background to create the character of artist Genevieve Planche in 'The Blue,' an 18th-century story of espionage in the porcelain workshops of England and France. In 'The Fugitive Colours,' published in 2022, Genevieve's story continues. Her new novel, 'The Orchid Hour,' is set in the speakeasies of NYC in 1923. Nancy lives with her family in the Hudson Valley in New York. Find out more at Nancy's website, NancyBilyeau.com and find her on Facebook and Twitter @Tudorscribe

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting