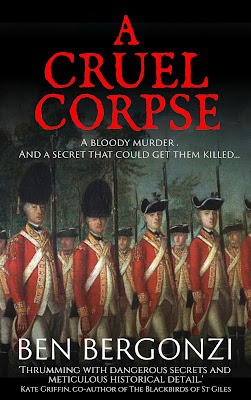

Carlisle, September 1747: A rebellion has been put down, but trouble persists for two soldiers in the government army. Jasper Greatheed is a man with a secret.

One day, over ten years ago, I took my children to see the Regimental Museum of the Warwickshire Fusiliers, which I had enjoyed so much at their age. That day I saw a new item on display, an 18th century print showing a woman in uniform. The caption said she was called Hannah Snell and that she had been a female soldier with the regiment in the 1740s.

Hanah Snell (Wikimedia Commons)

I was prompted to obtain a biography of Hannah, and then I read further about other female soldiers, sailors and civilians. These women confounded the era’s rigid division between male and female and all its rules of rank and behaviour. Thinking of the genre of historical crime, I conceived of a female detective who could adopt either male or female roles at will and so use her disguises to investigate crime.

For us today, the period where all women wore skirts and never trousers has disappeared from our living memory, so it is difficult for us today to imagine the severely normative effect of that dress code. But in the eighteenth century it seemed that there were several cases of women who wore breeches every day, and were more or less believed to be men. In the book I have Hayden say the line, ‘No one sees past the uniform,’ and I do believe that may have been true.

It’s interesting – and logical – to reflect that this was the one century when men were invariably clean shaven and either wore their hair long or used wigs.

Having devised this situation as a plot device, and conceived of Hayden Gray the soldier, who was formerly Grace Hayden the actress, and tested the concept in a short story which did well in a competition judged by the crime writer Howard Linskey, I then sat down to write the novel – then the trouble started.

I was determined to start on page one with my female soldier on duty in the army and with the murder victim already dead, so that the man killed should continue to present a danger even from his grave (It is because of his death that she has to turn detective so as to protect her own secret.) All this means that a lot of backstory has to be in place early on.

Perhaps echoing the questions we might ask of Hannah Snell or any of her contemporaries, why does Hayden choose to masquerade as a soldier? Who is helping her maintain her secret in a crowded barrack? And in terms of plot logic, what did Hayden do to earn the dislike of the dead man and his friend, the official investigator, the Provost Marshal?

I found an answer to the last question in the life of Hannah as related in her 1750 biography The Female Soldier. This book tells us that she was charged with ‘neglect of duty’ by a corrupt sergeant because she prevented him from raping a local woman, and that she was punished by flogging. I borrowed the same incident and made the corrupt sergeant the initial murder victim – the Cruel Corpse of my title.

However I dispensed with the flogging, as I did not think readers would believe that my heroine could remove her shirt and yet conceal her breasts, as reported in The Female Soldier. I replaced the flogging with a demotion, shown in flashback, from corporal to private.

Hayden’s reason to go into the army was resolved as a matter of debt, relating to the fact that she had earlier fallen foul of the always-fine distinction between acting and prostitution. Her helper in the army I decided would be the man who had recruited her in the first place. Here I conceived an entirely imaginary character, a bandsman orderly named Jasper who has the keeping of the medical stores, thus having an opportunity to safely hold Hayden’s female clothes, and indeed the supplies she needs to deal with menstruation.

I felt he should be a man accustomed to keeping secrets, and that she should be relaxed with him. Thus it became obvious that he should be a gay man, an ex-theatre colleague. The experience of a family member decided me to make him Black too.

Having the backstory in mind, successfully getting it into the book was very difficult. This caused a lot of rewriting, much of it having to be done from the query trenches. Eventually it dawned on me that I could use my secondary main character, Jasper, and his medical role, to introduce the body before I actually introduce Hayden. I also rewrote several scenes from her point of view to his, thus providing more about how she appears. This also helped me to ‘trickle in’ the backstory via flashbacks.

I also took from the Hannah Snell biography the city and castle of Carlisle, an isolated setting and one which, as my story starts, is still recovering from having been the only English city occupied by Jacobites in the 1745 Rebellion. The postwar setting, of garrison soldiers suddenly at peace but falling out amongst themselves, appealed to me for all sorts of reasons.

I think the eventual outcome is suspenseful, vivid and reasonably fair to the history, whilst being a crime novel first and foremost, not a discussion of transvestism, nor indeed a book solely from the female point of view (which is a tricky sell for a new male author.) If A Cruel Corpse does one thing, I hope it will appeal as much to the slim number of male readers of historical fiction as to the female readers.

Needless to say, Jasper and Hayden will return.

Ben Bergonzi

# # #

About the Author

Ben Bergonzi had a career in education and heritage, including spending time as a museum curator and as a manager of document digitization, Ben now works mainly as a reviewer and writer. He is a Reviews Editor for Historical Novels Review. Born in the north of England, he has spent most of his life in the midlands and the south; currently he lives with his family on the cusp of London and Chiltern Hills. His days as a re-enactor are long behind him, but he often remembers them while writing. You can find Ben on Twitter @BergonziBen and Bluesky @benbergonzi.bsky.social

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting