A vivid and powerful sequel to The Alchemy Thief. A tale of stolen secrets, kidnapping, slavery, and death.

Left behind as a slave in Morocco while Daniel journeys to the New World with the fearsome corsair Ayoub, Peri gives birth to a daughter. The drive to protect the imperiled lives of those she loves leads Peri to the court of the ruthless sultan, Moulay Ismail. In a city built on the backs of slaves, Peri’s rescue plot hangs by a thread, dependent on a dubious disguise and the man she despises. It will take all of her wit and perseverance to survive.

Tony, thank you so much for your interest in my Pirates and Puritans series!

The second book in the series, The Sultan’s Court takes place primarily in Morocco and New England in the years 1675-1676. During these years, the young sultan, Moulay Ismail fought to consolidate his power in Morocco. At the same time, New England was enveloped in the horror that was Metacom’s War (aka King Philip’s War.) Read on if you are curious how these two seemingly disparate events and places are connected!

Metacom was the sachem of the Wampanoag in America whom the English nicknamed King Philip. I was inspired to write The Sultan’s Court by stories of my ancestors who either fought or lost their lives during Metacom’s War, the bloodiest war per capita ever fought on North American soil.

In 1643, a group of Congregationalists (Puritans) traveled into the wilderness on the western frontier of the Plymouth Colony to found the English settlement of Rehoboth near Metacom’s Wampanoag village on Mount Hope. The first settlers of Rehoboth built their houses in the Ring of the Green, a circle of houses that was two and a half miles in circumference.

Many historians believe that although Metacom was planning to wage war, some young Wampanoags jumped the gun and started the war before Metacom was ready. At any rate, in June of 1675, while most settlers were in a church meeting, several Wampanoags were caught raiding homes outside Rehoboth, a teenager shot at them, they shot back, and the war was on.

My ancestors in Rehoboth lived in fear from the moment that first shot was fired. After burning several outlying homes, the Wampanoag were able to disappear in the “swamps,” where they knew how to live off the land, and then reappear without warning to ambush the settlers.

After some Wampanoag were captured or killed fighting the militia, Metacom and many of his men were able to escape north. The English colonists’ worst fear was realized when Metacom convinced other Native American groups to join him. Nipmucs attacked and burned Mendon to the north of Rehoboth. The war continued to expand.

In February of 1676, Reverend Noah Newman of Rehoboth wrote a letter containing harrowing tales of men, women, and children being slaughtered in Medfield, and requested that Plymouth send troops to protect Rehoboth, fearing a similar fate for his town.

While they waited for relief, fearful men slept with muskets by their sides, tended their fields in groups in which some guarded while others worked, and even prayed with their weapons in hand. They knew an attack would be forthcoming, they just didn’t know when.

Rumors of Indians gathering near Rehoboth grew. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, Plymouth Colony ordered that none of the inhabitants within the jurisdiction of Plymouth Colony were allowed to abandon their town under the penalty of forfeiture of their estates. My ancestors all stayed.

Plymouth sent about 60 militiamen and about 20 allied Indians to help defend the town. On March 26, 1676, the militia captain decided to go on the offensive and marched his army into the wilderness outside Rehoboth to root out the Indians.

The soldiers were led into a deadly ambush, surrounded by over 1000 Indian warriors, and suffered a devastating defeat. 3 soldiers and about 11 allied Indians escaped to tell the story. Two militiamen were captured, tortured, and killed after the battle.

Men from Rehoboth stumbled onto the field of dead bodies that had been stripped of their weapons, ammunition, supplies, and clothes. The full horror of their situation dawned on them. The defensive troops were dead. No other help was coming. The fewer than 400 men, women, and children of Rehoboth would have to defend themselves.

Many residents of Rehoboth rushed to Noah Newman’s home which had been turned into a garrison. My Fuller ancestors who lived on the Ring of the Green created a ruse, placing sharpened and blackened sticks around their house to make it appear from a distance to be heavily guarded. They hoped and prayed that the Indians would believe their home was a garrison and leave it alone.

The next day, Native American warriors spread out across the fields of Rehoboth and slaughtered the livestock, but they did not come near the garrison where the residents huddled together, waiting in dread. As night fell, the Indians disappeared, but the settlers knew they would be back.

The next morning, up to 1500 Indian warriors descended on the Ring of the Green and attacked, firing on the garrison, while whooping and yelling to increase the terror of the residents. The whole town was engulfed in flames.

Forty houses and thirty barns were burned. The gristmill, sawmill, and all the crops were destroyed. Miraculously in addition to the garrison houses, the Fuller’s house was left untouched. The ruse had worked. Besides the Fullers, five other families who lived on the Ring on the Green were my ancestors. They lost everything except their lives and the clothes on their backs.

The next day, the Native American warriors crossed the river and burned the town of Providence to the ground.

The Puritan culture encouraged community and charity, but the people in the frontier towns considered idleness a sin and would accept aid only as a last resort. Even so, as the spring wore on, the situation in Rehoboth was desperate.

On May 5, 1676, an elderly resident of Rehoboth wrote to a friend in Connecticut in secret, saying that “famine was staring them in the face.” In response to the letter, churches in the town of Hartford raised money to buy 600 bushels of wheat that were distributed to the people of Rehoboth so they would not starve.

But their misery was not over.

Five months after Rehoboth was burned, Metacom and his men circled back to the Rehoboth area. On August 12, 1676, Metacom was shot by an Indian allied with the English. He was beheaded and his body quartered. But Annawan, one of his chief captains remained at large until he was captured near Rehoboth on August 28.

This was the most deadly time for my ancestors because desperate warriors roamed the area. First Samuel Fuller was killed by Indians on August 15, then his brother John on August 23, and their mother, Sarah in October.

John Fuller left behind a pregnant wife and a 2-year-old, from whom I am descended. It is believed that John was collecting cedar wood when he was ambushed and killed. John Fuller’s young widow remarried and moved away to Plymouth, but when his young son came of age he returned to Rehoboth, rebuilt, and raised his family there.

But for the Wampanoags from neighboring Mount Hope, rebuilding their village was impossible. The land was sold to investors from Boston.

But what does any of this have to do with Morocco? My research uncovered an incredible story involving Native Americans who were captured or surrendered during the early stages of the war.

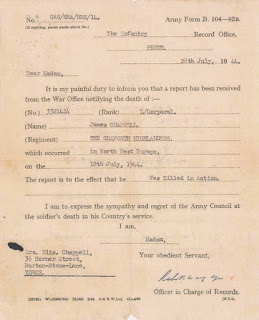

On September 28, 1675, a group of Native Americans was shipped to the West Indies. The ship was turned away from Barbados and went on to Cadiz, Spain. In a letter to the English Board of Admiralty, in December of 1675, Captain Thomas Hamilton stated that a group of Indians from America had been sent to him in Tangier, Morocco, to become slaves on the English galley, the Margaret.

The galley’s mission was to scour the Mediterranean to protect English shipping from Barbary corsairs. Hamilton had received thirty Native Americans, although nine had died. He was elated that the Indians were such good rowers, better than the “Moors,” and requested that more Indians be sent his way.

We have a list of names of some of those Indians. At one point, they were transferred to work on “the mole,” a breakwater the English were building to improve the harbor at Tangier. During the hasty evacuation of Tangier in 1684, the English blew up the mole and the harbor defenses, leaving the city to Sultan Moulay Ismail’s forces.

What became of the Native Americans sent to Tangier? In November of 1683, John Eliot, missionary to the Indians in New England, wrote a letter to Robert Boyle, the famous chemist in England, concerning the Indian captives in Tangier. They had sent a message to Eliot, asking him to find a way to return them home. Eliot asked Boyle for help. So we know they were still living in Tangier in1683.

Tangier Harbour (present day)

Did they escape on the high seas or during the confusion of the English retreat from Tangier in 1684? Were they brought back to England as slaves or captured by Moulay Ismail’s Moroccan troops who took over Tangier? Or did Robert Boyle somehow rescue them?

We may never know, but it is the perfect backdrop for my historical fiction novel, The Sultan’s Court.

R. A. Denny

# # #

About the Author

R.A. Denny is the author of two historical fiction and five fantasy novels. Readers have described her books as deep, spirited, and imaginative. After receiving her Juris Doctor from Duke University, she practiced criminal law for over twenty years. During that time, R.A. developed creative methods to educate the public about the law, presenting dramatic programs to over 300,000 people across the United States. She produced a full-length feature film that screened internationally. R.A. left the law to pursue her passion for writing. She had promised her mother she would finish the research they had begun in the Library of Congress when R.A. was 11 years old. One mysterious line about her 9th-great-grandfather led to years of research and a trip to Morocco. The result is R.A.’s latest novel,

The Alchemy Thief. An adventurous traveller, R.A. enjoys swimming, kayaking, and horseback riding. She delights in pursuing creative projects with her two adult sons and playing with her two young grandsons. Find out more at her

website and find her on

Goodreads and Twitter

@RADennyAuthor