England 1586: Alyce Bradley has few choices when her father decides it is time she marry as many refuse to see her as other than the girl she once was—unruly, outspoken and close to her grandmother, a woman suspected of witchcraft.

Today I'm pleased to welcome author Catherine Meyrick:

The poem didn’t manage to quite exorcise the experience and I started thinking of how dangerous it could be in other times, particularly if that gossip resulted in something like an accusation of witchcraft where normal evidential rules were set aside and the most dubious hearsay evidence could be enough to bring a person to the gallows.

Research

Like any historical novel, an immense amount of research was involved in writing The Bridled Tongue. As the novel is set in the same decade as Forsaking All Other, my previous novel, I was able to draw on my previous reading and the research I had done, not only to ensure that the story fitted into the historical timeline but that the details of clothing, housing and the minutiae of daily life were correct and especially that the characters were presented as people of their time, not modern people in period dress.

I based Alyce’s role at Ashthorpe, a fictional manor in Northhamptonshire, partly on Margaret, Lady Hoby (1571-1633), author of the earliest known diary written by a woman in English, who was almost an exemplar of the pious, sober and industrious gentlewoman of this period. Her diary provides a glimpse the busy domestic life of a woman managing a large household and estate, often in her husband’s absence.

Ashthorpe itself owed much to the Old Manor House at Glapthorn, Northamptonshire, leased by John Johnson, a draper and wool stapler, in 1544. The manor house’s surroundings included a formal knot garden, a kitchen garden, a fish pool with pike, perch and bream, and orchards of cherries, plums, and medlars and a walnut grove.

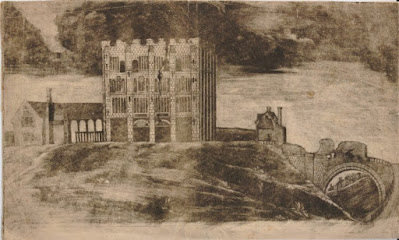

Norwich Castle was probably my biggest research challenge. The visit to Norwich gave me a strong sense of Norwich Castle as an imposing presence in the city. By the late sixteenth century, Norwich Castle was used as a prison, and one of my characters was imprisoned there. Although originally built as a royal palace, in 1220 it began to be used as a prison for felons and debtors and is believed to have been used as a gaol for state prisoners during the reign of Henry III. In 1345, it became the county gaol for Norfolk when Edward III gave it up as a royal palace. The castle then slowly fell into disrepair. The towers had begun to decay by the sixteenth century and part of the roof of the keep had fallen in. The earliest clear image I could find of the exterior was a drawing from 1662, 80 years after the setting of my novel.

Tell us something unexpected you discovered during your research

This is quite trivial but earrings do not really seem to have been a thing for most of the sixteenth century in England. I was in the revision stage for The Bridled Tongue when I read a blog post that said that Elizabethan women did not wear earrings. Sheer panic set in. In the novel a particularly lovely pair of earrings and a carcanet are given as a gift and both Alyce and her sister wear earrings regularly. If the blog post was correct, I would have to remove them.

Following my moments of panic, I spent an afternoon searching for images of sixteenth century women hopefully wearing earrings so that I could ignore what I had read. There are plenty of images of women wearing earrings throughout the sixteenth century but up until the last couple of decades these are mainly pictures from Spain and Italy. The only woman I could find wearing them in England in the 1570s was Mary, Queen of Scots.

I looked at sixteenth century Englishmen’s ears too and was surprised to find them disappointingly unadorned for most of the century. I found one portrait from the late 1570s with an earring (Sir George Gill of Wyddial Hall, Hertfordshire), one from the 1580s (a 1588 portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh sporting a lovely pair of pearls in one ear) and several from the early 1590s but, mostly, the peacocks of Elizabeth’s age have naked ears, even Robert Dudley. As my story is set in the mid to late 1580s, I decided that the women’s earrings could stay because, at a stretch, I could argue that they were growing in popularity through the 1580s but I did a purge of any mention of baubles hanging from men’s ears.

What are you planning to write next?

With my next novel, due out at the end of April, I have stepped away from the Elizabethans and have written about Hobart, Tasmania between 1878 and 1885. Cold Blows the Wind is based on a period in the lives of my paternal great-great-grandparents, Ellen Thompson and Harry Woods. It is the result of my own genealogical research as their story was basically unknown until I uncovered it through my family history digging ten to fifteen years ago.

After that, I will probably stay close to home with my writing. I am contemplating something set in my own suburb in the aftermath of World War 1. While, in some ways Cold Blows the Wind has been the most difficult thing I have ever written, I have enjoyed writing in the type of Australian English spoken by my grandfather who was born in 1887. I also haven’t had to worry about working out which season is when, what the weather is like or where the sun sits in the sky.

Catherine Meyrick is an Australian writer of romantic historical fiction. Until recently she worked as a customer service librarian at her local library. She has a Master of Arts in history and is also an obsessive genealogist. Find out more at Catherine’s website https://catherinemeyrick.com/ and follow her on Facebook and Twitter @cameyrick1.

Catherine Meyrick is an Australian writer of romantic historical fiction. Until recently she worked as a customer service librarian at her local library. She has a Master of Arts in history and is also an obsessive genealogist. Find out more at Catherine’s website https://catherinemeyrick.com/ and follow her on Facebook and Twitter @cameyrick1.

Please tell us about your latest book

The Bridled Tongue begins in 1586 and follows the life of Alyce Bradley, the daughter of a wealthy Norwich mercer, as she adjusts to an arranged marriage to a privateer, Thomas Granville. This is not a marriage she particularly wishes for but one she has agreed to because she believes she has no other options. It shows the way she grows into her role of manor wife and the dangers she faces not only from her husband’s enemies but her own past when long buried resentments are stirred to life along with old slanders concerning her relationship with her grandmother, thought by some to be a witch. The backdrop is the threat of immanent invasion by the Spanish in 1588.

It is a standalone novel and while the major characters are fictional, they do rub shoulders with some historical personages. The timeline and background are as accurate as I could make them. Alyce is an intelligent but reasonably conventional young woman of the middling sort and while she questions why life cannot offer her more opportunities and why the same standards are not expected of men as of women, she ultimately accepts her society’s rules and expectations.

By making my characters conventional, I hoped to show something of the reality of lives in the past, the lack of freedom that women, and men as well, had in determining their own lives and even their choice of spouse. I also wanted to look at the way gossip and slander can spiral out of control and the effect on women’s relationships when they are valued mainly for their ability to produce healthy children.

Inspiration

The spark, many years ago, was my own experience as the subject of gossip. What struck me was the way a minor incident or slip of the tongue can be twisted, embellished and shaped into something else altogether. It is a most uncomfortable experience and I tried to get it out of my system by writing a poem called ‘the coven’. I entered it in a poetry competition run by the Tuggerah branch of the Fellowship of Australian Writers. It won first prize in the free verse section of their Joan Johnson Poetry Award. As well as a monetary prize, I received a small trophy of which I am inordinately proud – not being a sporty type, it is my only trophy.

The poem didn’t manage to quite exorcise the experience and I started thinking of how dangerous it could be in other times, particularly if that gossip resulted in something like an accusation of witchcraft where normal evidential rules were set aside and the most dubious hearsay evidence could be enough to bring a person to the gallows.

Research

Like any historical novel, an immense amount of research was involved in writing The Bridled Tongue. As the novel is set in the same decade as Forsaking All Other, my previous novel, I was able to draw on my previous reading and the research I had done, not only to ensure that the story fitted into the historical timeline but that the details of clothing, housing and the minutiae of daily life were correct and especially that the characters were presented as people of their time, not modern people in period dress.

I based Alyce’s role at Ashthorpe, a fictional manor in Northhamptonshire, partly on Margaret, Lady Hoby (1571-1633), author of the earliest known diary written by a woman in English, who was almost an exemplar of the pious, sober and industrious gentlewoman of this period. Her diary provides a glimpse the busy domestic life of a woman managing a large household and estate, often in her husband’s absence.

It also gives a strong sense of the breadth of skills possessed by women in these positions, from entertaining guests, sewing and preserving foods to pulling hemp, weighing and dying wool and spinning as well as distilling medicinal salves and tinctures and providing medical care for the household and tenants, keeping the accounts, managing the wider farm and playing a role in keeping the Manor Court, sometimes even when her husband was at home. Many women, no doubt, found a sense of purpose managing such large enterprises.

Ashthorpe itself owed much to the Old Manor House at Glapthorn, Northamptonshire, leased by John Johnson, a draper and wool stapler, in 1544. The manor house’s surroundings included a formal knot garden, a kitchen garden, a fish pool with pike, perch and bream, and orchards of cherries, plums, and medlars and a walnut grove.

We know a great deal about the life of John Johnson and his wife Sabine Saunders at Glapthorn because John became bankrupt in March 1553 and his papers and account books were forwarded to the Privy Council and so have survived, allowing us a glimpse not only of the business but the personal life of a Tudor merchant family. Barbara Winchester (1924-1963) transcribed the Johnson letters as part of her PhD thesis in 1953. Volume 1 of her thesis, modified for general readers and published as Tudor Family Portrait in 1955, was also invaluable in giving me a sense of the daily life of a manor wife in the sixteenth century.

This sort of research is relatively straightforward but gaining a sense of place is critically important to historical fiction, it is where our characters live and breathe. When I first started writing The Bridled Tongue, I had never left Australia, so it was a bit of the challenge. I began reading everything I could lay my hands on about the history of Norwich where part of the story is set, including travellers’ descriptions of their visits in later periods.

I pored over contemporary maps, but they are often not as helpful as they could be and are more ‘picture maps’ than accurate cartography. In William Cuningham’s 1558 map, not only are a number of churches missing but also the important public building, the Guildhall. I looked at drawings of the buildings and made use of online interactive 360-degree panoramas of the modern city. Fortunately, in 2016, I was able to visit Norwich during my first trip to the northern hemisphere.

I walked around Elm Hill, with its cobbled streets and Tudor buildings, imagining how Alyce would have felt in this place, trying to strip away the changes of the last four hundred and thirty years. I didn’t get to go inside the Guildhall but found an interactive panorama of its interior – the Mayor’s Court is still set out and furnished as a Tudor courtroom.

Norwich Castle was probably my biggest research challenge. The visit to Norwich gave me a strong sense of Norwich Castle as an imposing presence in the city. By the late sixteenth century, Norwich Castle was used as a prison, and one of my characters was imprisoned there. Although originally built as a royal palace, in 1220 it began to be used as a prison for felons and debtors and is believed to have been used as a gaol for state prisoners during the reign of Henry III. In 1345, it became the county gaol for Norfolk when Edward III gave it up as a royal palace. The castle then slowly fell into disrepair. The towers had begun to decay by the sixteenth century and part of the roof of the keep had fallen in. The earliest clear image I could find of the exterior was a drawing from 1662, 80 years after the setting of my novel.

Norwich Castle, 1662

The interior of the castle had changed so much over the centuries that even visiting the dungeons, I found it difficult to get a real sense of what it was like as a prison. While most histories of the castle provide detail of the early period and presumed arrangement of the interior, the later period up to the 1770s is glided over.

Through the magic of Google Books, I found a 1796 article published in Archaeologia: Or Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity by William Wilkins, Norwich architect, classical scholar and archaeologist who later designed the new prison at the Castle. In it he said, ‘The inside of the castle has been so much altered, from having been long used as a county gaol, that little can be said, or even conjectured, of the original plan, and the various uses of the rooms.’ If they had no idea at the end of the eighteenth century, what hope did I have? I took that as licence to give up my search and fill in the gaps with a, hopefully, informed imagination.

But I could not imagine the Tudors, with their strong sense of a God-given hierarchy, being content with wealthy, well-born prisoners being consigned to dilapidated cells with the common sort, no matter what their crime. Serendipity came to my rescue. When looking for something else, I stumbled across a booklet called Notes Concerning Norwich Castle written before 1728 by John Kirkpatrick, the Norwich antiquary. Kirkpatrick’s notes do not describe the inner arrangement of the castle but he does mention speaking with an elderly woman, Mrs Burrows , an ‘old inhabitant of St. John’s Timberhill parish’ whose father ‘kept the county gaol for several years, and dwelt in the house called the Golden ball, where the better sort of prisoners who had money, lodged then, and not in the Castle (as had before been used in the house which is on the other side of the lane, opposite to the Ball, which was therefore called the old gaol)’. It is quite conceivable that this was the situation in the sixteenth century as well. This was the only mention I could find of the ‘Golden ball’ house so it was time to put imagination to work again.

Compared to this, researching witchcraft accusations and trials was simple. Several books were invaluable in providing understanding and structure before I looked at the many contemporary pamphlets available online. These include among many, many others Gregory Durston’s Crimen Exceptum: The English Witch Prosecution in Context (2019) and Witchcraft and Witch Trials: a History of English Witchcraft and its Legal Perspectives, 1542 to 1736 (2000), Barbara Rosen’s Witchcraft in England, 1558-1618 (1991) and James Sharpe’s Instruments of Darkness: Witchcraft in Early Modern England (1996). For the legal process at the time, I relied on Sir Thomas Smith’s De Republica Anglorum (1583, 1982 edn.). In all this I have been truly fortunate that the State Library of Victoria provides the ordinary person online access from home to a massive range of academic journals and the National Library of Australia access to Early English Books Online.

Tell us something unexpected you discovered during your research

This is quite trivial but earrings do not really seem to have been a thing for most of the sixteenth century in England. I was in the revision stage for The Bridled Tongue when I read a blog post that said that Elizabethan women did not wear earrings. Sheer panic set in. In the novel a particularly lovely pair of earrings and a carcanet are given as a gift and both Alyce and her sister wear earrings regularly. If the blog post was correct, I would have to remove them.

Following my moments of panic, I spent an afternoon searching for images of sixteenth century women hopefully wearing earrings so that I could ignore what I had read. There are plenty of images of women wearing earrings throughout the sixteenth century but up until the last couple of decades these are mainly pictures from Spain and Italy. The only woman I could find wearing them in England in the 1570s was Mary, Queen of Scots.

Elizabeth 1 (Kirchner portrait 1580)

In the early part of Elizabeth’s reign, it is impossible to tell if they were worn because of the coifs and caps and ear-high ruffs. From the 1580s, before earrings appear with any frequency, there are images of women wearing baubles in their hair near the ears. By the end of the 1590s earrings are common but not ubiquitous.

I looked at sixteenth century Englishmen’s ears too and was surprised to find them disappointingly unadorned for most of the century. I found one portrait from the late 1570s with an earring (Sir George Gill of Wyddial Hall, Hertfordshire), one from the 1580s (a 1588 portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh sporting a lovely pair of pearls in one ear) and several from the early 1590s but, mostly, the peacocks of Elizabeth’s age have naked ears, even Robert Dudley. As my story is set in the mid to late 1580s, I decided that the women’s earrings could stay because, at a stretch, I could argue that they were growing in popularity through the 1580s but I did a purge of any mention of baubles hanging from men’s ears.

What are you planning to write next?

With my next novel, due out at the end of April, I have stepped away from the Elizabethans and have written about Hobart, Tasmania between 1878 and 1885. Cold Blows the Wind is based on a period in the lives of my paternal great-great-grandparents, Ellen Thompson and Harry Woods. It is the result of my own genealogical research as their story was basically unknown until I uncovered it through my family history digging ten to fifteen years ago.

They were both the children of convicts transported to Van Diemen’s Land and like so many men and women in the nineteenth century, lacking money and influence, their lives were precarious and they did not have much use for the middle-class virtues we see as ‘Victorian’. At this time Hobart was a vibrant town drawing people from every corner of the earth where, because of the recent past, a person’s history wasn’t closely questioned. The story touches on such issues as secrets, family ties, poverty, and the struggles of unmarried mothers.

I am hoping to show just how hard life was for these people, women in particular. Cold Blows the Wind is not a romance but it is a story of love – a mother’s love for her children, a woman’s love for her family and, those most troublesome loves of all, for the men in her life. It is a story of the enduring strength of the human spirit.

After that, I will probably stay close to home with my writing. I am contemplating something set in my own suburb in the aftermath of World War 1. While, in some ways Cold Blows the Wind has been the most difficult thing I have ever written, I have enjoyed writing in the type of Australian English spoken by my grandfather who was born in 1887. I also haven’t had to worry about working out which season is when, what the weather is like or where the sun sits in the sky.

Catherine Meyrick

# # #

About the Author

Catherine Meyrick is an Australian writer of romantic historical fiction. Until recently she worked as a customer service librarian at her local library. She has a Master of Arts in history and is also an obsessive genealogist. Find out more at Catherine’s website https://catherinemeyrick.com/ and follow her on Facebook and Twitter @cameyrick1.

Catherine Meyrick is an Australian writer of romantic historical fiction. Until recently she worked as a customer service librarian at her local library. She has a Master of Arts in history and is also an obsessive genealogist. Find out more at Catherine’s website https://catherinemeyrick.com/ and follow her on Facebook and Twitter @cameyrick1.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting